Depreciation and amortisation are accounting techniques used to allocate the depreciable amount (i.e., cost less residual value) of tangible and intangible assets over their respective useful lives. Depreciation begins when an asset is ready for use and ends when the asset is derecognised or classified as held for sale. The chosen depreciation method should reflect the pattern in which the future economic benefits of the asset are expected to be consumed. Available methods include the straight-line method, the diminishing balance method, and the units of production method. The depreciation charge for each period should be recognised in profit or loss, unless it’s factored into the carrying amount of another asset.

Let’s explore this in more depth.

Depreciation vs amortisation

The term ‘depreciation’ is typically associated with tangible assets like property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), while ‘amortisation’ refers to intangible assets. The requirements for depreciating PP&E are found in IAS 16, whereas IAS 38 deals with the amortisation of intangible assets. Most requirements of these two standards overlap with a few noteworthy exceptions that are separately discussed where applicable. Unless otherwise stated, all discussions on this page are equally relevant to both tangible and intangible assets.

Depreciable amount

The depreciable amount is defined as the difference between an asset’s cost and its residual value. The asset’s residual value is the anticipated amount that an entity would currently obtain from selling the asset in its expected end-of-life condition, after accounting for any estimated disposal costs (IAS 16.6).

An increase in an asset’s residual value arising from past events will reduce the depreciable amount. However, the purpose of depreciation is not to recognise a decrease in the asset’s value but rather to allocate its cost over its useful life. Therefore, expected changes in residual value unrelated to the expected wear and tear of the asset should not be considered in determining the depreciable amount (IAS 16.BC29). Consequently, depreciation is recognised even if the fair value of the asset exceeds its carrying amount, provided the asset’s residual value does not exceed the carrying amount (IAS 16.52,54).

In the majority of cases, the residual value is negligible, and an asset is depreciated until its carrying amount is zero (IAS 16.53). Moreover, IAS 38.100 presumes that the residual value of an intangible asset should be assumed as zero unless there is a commitment by a third party to purchase the asset at the end of its useful life or there is an active market for the asset.

--Are you tired of the constant stream of IFRS updates? I know it's tough! That's why I created Reporting Period – a once-a-month summary for professional accountants. It consolidates all essential IFRS developments and Big 4 insights into one readable email. I personally curate every issue to ensure it's packed with the most relevant information, delivered straight to your inbox. It's free, with no spam, and you can unsubscribe with just one click. Ready to give it a try?

Depreciation period (useful life)

Depreciation begins when the asset is in ‘the location and condition necessary for it to be capable of operating in the manner intended by management’ (IAS 16.55, IAS 38.97). This point is also the cut-off for recognising directly attributable costs as part of the asset’s cost. Even if the asset remains unused, depreciation charges should still be applied.

The useful life of an asset, over which depreciation occurs, is the duration for which an asset is expected to be available for use by the entity (IAS 16.6). The useful life should be specific to the entity and can be considerably shorter than the life span determined by others. It is dictated by the entity’s activity profile and its asset management policy (IAS 16.57). The useful life can also be represented by the estimated number of production units or similar outputs expected from the asset. Factors to consider in determining the useful life are listed in IAS 16.56.

IFRSs allow significant discretion in determining useful life. For instance, if an entity intends to alter its operational profile and use an asset longer than initially expected, it can extend the useful life of an asset, even if the planned changes necessitate investments in other assets to which the entity has not yet committed.

Depreciation of unused assets

Depreciation commences when an asset is in the location and condition necessary for operation as intended by management. Even if an asset is not used during a period, it is still depreciated unless the units of production method is applied to that asset (IAS 16.55). The depreciation charge for that period reflects the consumption of the asset’s service potential occurring while the asset is held (IAS 16.BC31). Such ‘idle’ periods typically occur just after the asset’s acquisition or development and just before its disposal.

In some instances, an asset is intended to be used only alongside other assets that are not yet ready for use. In such scenarios, it is necessary to exercise judgement to determine the point at which the consumption of the future economic benefits embedded in that asset begins, which will, in turn, dictate when depreciation should start. There are two acceptable approaches to determining when depreciation should commence.

The first approach is to begin depreciation when the group of assets, to which the specific asset belongs, is collectively ready to start operations. This is because the realisation of the future economic benefits embedded in the asset effectively starts from this point. The second approach focuses on the individual asset’s readiness for use, independent of the asset group. According to this method, depreciation begins from the date the asset is considered available for use on a standalone basis.

Note that assets under the scope of IFRS 5 are not depreciated. See also impairment implications for unused assets.

Useful life and amortisation period of intangible assets

IAS 38 requires entities to determine whether an intangible asset has a finite or indefinite useful life. An intangible asset is considered as having an indefinite (not to be confused with infinite) useful life when there is no foreseeable limit to the period during which the asset is expected to generate net cash inflows for the entity (IAS 38.88). More guidance on making this distinction, including considering only those renewals that can be effected without substantial cost, can be found in paragraphs IAS 38.90-96.

Common examples of assets with indefinite useful lives are well-established brands and licences with unlimited duration or with renewals that don’t involve significant cost. On the other hand, assets with finite useful lives usually include rights with a finite duration (e.g., licences, patents), software, know-how, newly developed brands, and customer relationships. Intangible assets with finite useful lives are amortised over their useful lives. The requirements for the amortisation period and method are set out in paragraphs IAS 38.97-99 and generally align with those in IAS 16.

An intangible asset with an indefinite useful life is not amortised. Instead, it should be tested for impairment annually under IAS 36 (IAS 38.107-108). Additionally, the assessment of whether an intangible asset has an indefinite useful life should be reviewed at each reporting date (IAS 38.109-110).

For further guidance, refer to Examples 4-9 accompanying IAS 38.

Depreciation method

Choosing depreciation method

The depreciation method should systematically allocate an asset’s depreciable amount over its useful life, reflecting the pattern in which the asset’s future economic benefits are expected to be consumed by the entity (IAS 16.60). The most commonly used depreciation methods are:

- Straight-line method.

- Diminishing balance method.

- Units of production method.

However, an entity may select its own method that best reflects the consumption of the economic benefits of an asset.

Straight-line method

The straight-line method is the most widely employed method of depreciation. As suggested by the name, the depreciation charge is distributed evenly over the asset’s useful life, making it appropriate for the majority of assets.

Diminishing balance method

The diminishing balance method (also known as the reducing balance method) sees the depreciation charge decrease over time as it is calculated based on the carrying value of the asset at the beginning of the current period, not its original cost. This method is used for assets susceptible to increased technical or commercial obsolescence.

There are various approaches to the application of this method. In essence, a depreciation rate is applied to the net book value (carrying amount) of the asset, rather than its original cost (as with the straight-line method). When the asset has a residual value, the same depreciation rate can be applied throughout its useful life. This depreciation rate can be calculated using the ‘goal seek’ function in Excel (an illustrative Excel file can be found in the example below). If there is no residual value, achieving zero at the end of the useful life using the same depreciation rate applied to the net book value for the entire depreciation period isn’t possible. In such cases, the diminishing balance method switches to the straight-line method when the depreciation charge under the straight-line method is greater than it would be under the diminishing balance method.

The following examples demonstrate these two approaches to the diminishing balance method.

Example: Diminishing balance depreciation with residual value

An entity purchased a piece of high-tech PP&E subject to increased technical obsolescence for $12 million. The entity estimates that the asset will be used for five years, with most of its performance utilised in the early years. The residual value is $2 million. The depreciation is calculated using the diminishing balance method as shown below. Please note that the depreciation rate is calculated using the ‘goal seek’ function. You can download an Excel file for this example.

| Year | Net book value | Depreciation charge |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.00 | 3.61 |

| 2 | 8.39 | 2.53 |

| 3 | 5.86 | 1.76 |

| 4 | 4.09 | 1.23 |

| 5 | 2.86 | 0.86 |

| Residual value | 2.00 |

Example: Diminishing balance depreciation without residual value

The entity purchased the same asset as in the example above, but this time the residual value is zero:

- Rate for diminishing balance depreciation: 30%

- Rate for straight-line depreciation: 20%

- Cost of PP&E: $12m

- Depreciation charge under straight-line depreciation: $2.4m

- Residual value: $0m

You can download an Excel file for this example.

| Year | Net book value | Depreciation charge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.00 | 3.60 | @ Diminishing balance rate |

| 2 | 8.40 | 2.52 | @ Diminishing balance rate |

| 3 | 5.88 | 2.40 | @ Straight line rate |

| 4 | 3.48 | 2.40 | @ Straight line rate |

| 5 | 1.08 | 1.08 | @ Straight line rate (until NBV = 0) |

| Residual value | 0.00 |

Sum of the digits depreciation

The sum-of-the-digits depreciation method, akin to the diminishing balance method, is explained with an example below.

For this example, we use the same high-tech PP&E item purchased for $12 million with no residual value, to be used over five years. The entity recognises the depreciation expense using the sum of the digits method as follows:

- Year 1: (5/15) x $12m = $4m

- Year 2: (4/15) x $12m = $3.2m

- Year 3: (3/15) x $12m = $2.4m

- Year 4: (2/15) x $12m = $1.6m

- Year 5: (1/15) x $12m = $0.8m

- Total: $12m

You can download an Excel file detailing these calculations.

Units of production method

This method bases depreciation on an asset’s expected use or output. The depreciation charge for a period reflects the proportion of total expected use or output consumed during that period. A depreciation or amortisation method based on revenue generated by an activity involving the use of an asset is permitted, under limited circumstances, exclusively for intangible assets, as outlined in IAS 38.98A-C. This is because revenue can be affected by other inputs and processes, sales activities, and changes in sales volumes and prices (IAS 16.62A).

Depreciation based on tax allowances

Some entities choose to depreciate assets based on the depreciation tax allowance specified by the tax law for a particular asset. Under IFRS, this approach can be adopted only if such depreciation also reflects the pattern in which the asset’s future economic benefits are expected to be consumed by the entity. Special caution is necessary when tax laws encourage expenditures on certain types of assets by permitting accelerated tax depreciation. In such cases, tax depreciation rates rarely reflect the pattern in which the entity is expected to consume the asset’s future economic benefits faithfully.

Separate depreciation of significant parts of PP&E

Each part of a PP&E item with a cost that is significant in relation to the total cost should be depreciated separately (IAS 16.43-47). An example given by IAS 16.44 uses the airframe and engines of an aircraft, which should be depreciated separately. IAS 38 does not introduce separate amortisation of significant parts of an intangible asset.

Land and buildings

Separate depreciation is particularly relevant when considering land and buildings. Often, it’s not feasible to legally separate buildings from the land they’re located on. However, they should be considered as separate assets and depreciated independently. Land, unlike buildings, has an infinite useful life (with limited exceptions) and should not be depreciated. When determining residual values, buildings should also be separated from land, thus an increase in the value of land should not impact the depreciation of buildings (IAS 16.58).

In some instances, the cost of land includes decommissioning costs. These costs are depreciated over the period of benefits derived from incurring them, such as until the expected restoration takes place (IAS 16.59).

Changes in estimates

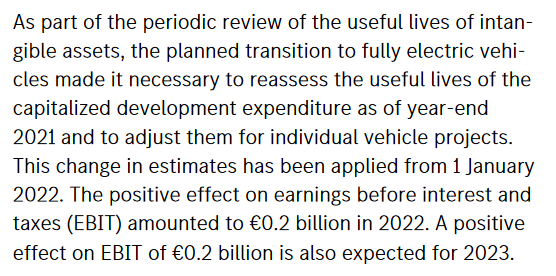

The residual value, useful life, and depreciation method should be reviewed at least at the end of each financial year (IAS 16.51,61; IAS 38.104-106), with any changes accounted for prospectively under IAS 8 as changes in accounting estimates. The extract below illustrates a disclosure relating to a change in estimated useful lives of intangible assets:

More about IAS 16 and 38

See other pages relating to IAS 16 and IAS 38:

IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment: Scope, Definitions and Disclosure

IAS 38 Intangible Assets: Scope, Definitions and Disclosure

IAS 16: Cost of Property, Plant and Equipment

IAS 38: Recognition and Cost of Intangible Assets

IAS 16 and IAS 38: Revaluation Model for Property Plant and Equipment and Intangible Assets