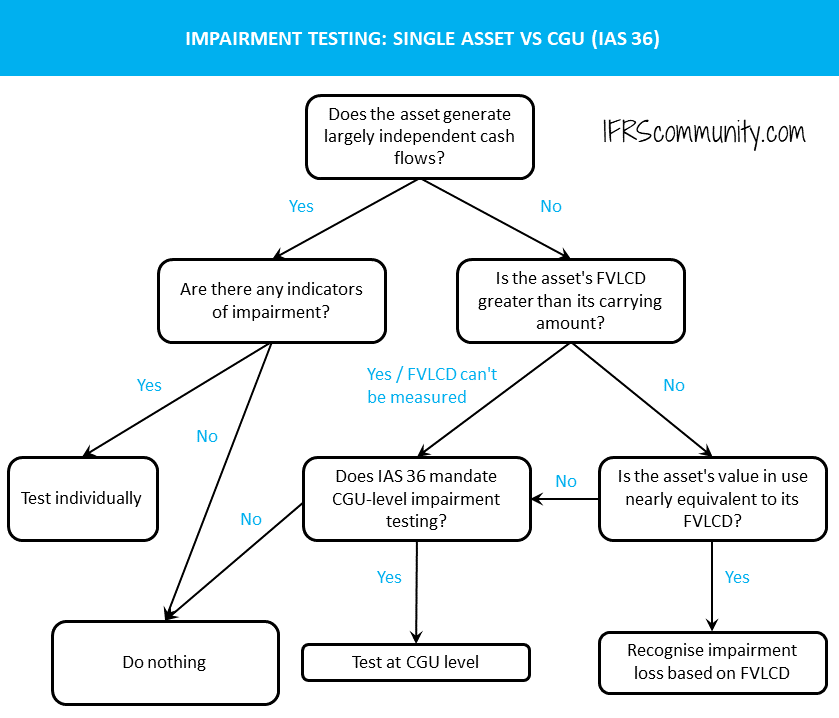

Assets should undergo impairment testing individually where feasible. However, testing a single asset for impairment is often impracticable, necessitating the grouping of assets into cash-generating units (CGUs) as per IAS 36.66. The following decision tree aids in determining which assets require individual impairment testing and which should be assessed at the CGU level:

Are you tired of the constant stream of IFRS updates? I know it's tough! That's why I created Reporting Period – a once-a-month summary for professional accountants. It consolidates all essential IFRS developments and Big 4 insights into one readable email. I personally curate every issue to ensure it's packed with the most relevant information, delivered straight to your inbox. It's free, with no spam, and you can unsubscribe with just one click. Ready to give it a try?

Defining a CGU

According to IAS 36.22, the recoverable amount of an asset is determined individually unless the asset’s cash inflows are not largely independent from those of other assets. In such instances, the recoverable amount is calculated for the CGU encompassing the asset, except when:

- The asset’s fair value less costs of disposal (FVLCD) exceeds its carrying amount; or

- The asset’s value in use (ViU) can be estimated to be close to its FVLCD, and this fair value can be measured.

Thus, a CGU comprises assets (IAS 36.67):

- That generate cash inflows not largely independent of other assets; and

- Whose ViU cannot be estimated to be close to its FVLCD, especially when significant cash inflows are expected from their continued use.

Examples of CGUs include:

- Individual stores or store chains in the retail sector;

- Individual properties in the real estate sector;

- Service lines in the technology industry like cloud computing, cybersecurity, or data analytics;

- Product lines in the technology industry like smartphones, laptops, or software solutions

- Business units like retail banking, investment banking, or asset management in the financial sector;

- Hotels, resorts or theme parks in the hospitality and entertainment industry;

- Content divisions like film production, television, and streaming services in the media industry;

- Oil fields in the energy sector.

Identification of CGUs must remain consistent across reporting periods, unless a revision is warranted (IAS 36.72-73).

Example: Asset pending replacement

Crystal Clear Solutions, a manufacturer supplying the construction industry, has a CGU that includes a window production facility. The firm plans to invest $900k in new window handle machinery due to the diminished efficiency of the existing equipment, which is to be replaced shortly. Despite being operational, the old machinery is valued by management at $300k, while its book value stands at $400k.

Given the brief duration of its remaining usage, the machinery’s value in use is assessed to be close to its FVLCD. Hence, although the entire plant is not impaired, a $100k impairment loss is recognised for the handle machinery. When evaluating the plant’s CGU for impairment, the old machinery’s book value is omitted, but the forthcoming $900k replacement cost is factored into the future cash flows.

Example: Decline in asset value

Blue Horizon, an influential consultancy with a global footprint, classifies each country operation as a separate CGU without any associated goodwill on its statement of financial position.

In China, Blue Horizon owns an iconic office in Shanghai’s financial sector, underscoring its regional dedication and serving as an operational hub. Despite the company’s profitable Chinese division and the success of its advisory services, the property market’s instability has led to a marked downturn in real estate values, including Blue Horizon’s premises.

Nonetheless, the firm’s Chinese operations maintain strong cash generation. Accordingly, the company determines that:

- The office’s cash inflows are not independent of other assets;

- Its FVLCD is lower than its carrying amount; but

- Its value in use cannot be estimated to be close to its FVLCD.

As a result, Blue Horizon does not recognise an impairment loss on the office. Assuming no indicators of impairment, the company also refrains from conducting an impairment test on the China CGU.

Understanding independent cash inflows

It is vital to note that IAS 36 underlines the significance of independent cash inflows rather than all cash flows. Consequently, centralised functions such as procurement, or the operations of shared service centres, do not influence the determination of CGUs.

Example: Retail outlet

Consider Silk Constellation, a retail store within the Twilight Tailors chain. Despite centralised procurement and strategic decisions, Silk Constellation operates in a distinct neighbourhood with a unique customer base, separate from Twilight Tailors’ other outlets in the vicinity and nationwide. Due to its ability to generate cash inflows largely independently from other stores, Silk Constellation is identified as an individual CGU.

Unused (idle) assets

Consider FloraTech Corp which owns a warehouse that is a part of Garden Essence CGU. Due to changes in the production process, the warehouse is no longer in use, standing vacant. However, Garden Essence CGU isn’t impaired.

Can the warehouse, now unused, remain a part of Garden Essence CGU?

The answer is no. Since the warehouse no longer generates cash inflows that are dependent on other assets of Garden Essence, its value in use can be estimated to be close to its fair value less costs of disposal. Consequently, the warehouse should undergo a separate impairment test. Since it’s not generating any cash inflows, the recoverable amount will be based on its FVLCD. This is further discussed in the footnote to IFRS 5.4.

Active market for the output produced

IAS 36.70 stipulates that assets should be designated as a CGU if there exists an active market for their output. This applies even when the output is utilised internally, as often seen in vertically integrated entities. An active market, as defined in IFRS 13, is characterised by transactions for an asset occurring frequently and voluminously enough to provide pricing information on an ongoing basis. For non-financial assets, active markets are typically found in sectors like energy (e.g., crude oil, natural gas), metals (e.g., gold, copper) or agriculture (e.g., corn, soybeans, coffee).

Refer to Example 1 (cases B and C) in IAS 36, which illustrates this point.

CGU identification on a country-by-country basis

Multinational groups generally authorise local subsidiary (or sub-group) management to make autonomous decisions concerning market operations within their territories. These subsidiaries, for statutory IFRS reporting purposes, tend to identify several CGUs. Conversely, parent companies, in their consolidated financial statements, may opt to view each country or subsidiary as a single CGU. This perspective is a practical simplification based on materiality. It would be challenging to conceptually justify why locally identified CGUs wouldn’t have independent cash inflows from the group’s viewpoint.

Corporate assets

Corporate assets, often referred to as ‘shared’ assets, include resources like a headquarters building or IT systems that support the entire group or several divisions but do not directly generate independent cash inflows. Consequently, these assets cannot be wholly assigned to a single CGU.

In the context of impairment testing, it’s essential for companies to identify every corporate asset that plays a part in the performance of the CGU being assessed. When it’s feasible to allocate a part of a corporate asset’s value to a CGU in a manner that is both reasonable and consistent, this should be incorporated into the impairment test.

However, IAS 36 doesn’t specify the criteria for ‘reasonable and consistent’ allocation, leaving companies to rely on their judgement. For instance, Example 8 in IAS 36 (IAS 36.IE70) uses relative carrying amounts of the CGUs as a reasonable indication of the proportion of a corporate asset devoted to each unit. In cases where corporate assets are distinct legal entities, intercompany billing might provide a foundation for allocation. When a CGU faces an impairment loss, this loss should be allocated to the corporate assets on a proportional basis along with the other assets in the CGU.

If ‘reasonable and consistent’ allocation is not achievable, the impairment review should be conducted at the smallest collection of CGUs where such allocation is possible (IAS 36.100-103). Refer also ‘Sequence of impairment tests’ below and to Illustrative Example 8 from IAS 36.

Goodwill

Goodwill, for the purposes of impairment testing, must be allocated to the CGU that derives benefits from the synergies of the corresponding business combination. In cases where it’s impractical to assign goodwill to individual CGUs in a non-arbitrary manner, it should then be allocated to groups of CGUs. It’s noteworthy that there are scenarios in which a pre-existing CGU gains advantages from a business combination, even though the newly acquired assets are not directly assigned to it. The CGU, or the group of CGUs, receiving the allocation of goodwill must be smaller than or equal to the size of an operating segment as outlined in IFRS 8, before aggregation. Although not explicitly mentioned in IAS 36, this stipulation is also applicable to entities that do not have publicly traded debt or equity instruments and are, consequently, not required to report segment information as per IFRS 8. Lastly, the allocation of goodwill should align with the lowest level at which goodwill is monitored for internal management purposes (IAS 36.80-87).

IAS 36 does not elaborate on allocating goodwill’s carrying amount to individual CGUs. Typically, the practice is to allocate goodwill based on the proportionate recoverable values of the assets within the CGUs. However, other methods are also acceptable, such as allocation based on the change in fair values of CGUs before and after the business combination.

In cases where the initial allocation of goodwill cannot be finalised within the annual period of the business combination, it must be completed within the first annual period post-acquisition (IAS 36.84-85).

Regarding the sale of an operation within a CGU to which goodwill has been allocated, a proportion of goodwill should be factored into the carrying amount of the net assets sold. The portion of goodwill considered ‘sold’ should be calculated based on the relative values of the operation being sold compared to the remaining CGU. However, if a more accurate reflection of the goodwill linked to the disposed operation is achievable, an alternative method may be employed. While IAS 36 does not detail the calculation of these ‘relative values’, the recoverable amounts are commonly used in practice.

Sequence of impairment tests and allocation of losses

The sequence for conducting impairment tests can become complex when corporate assets and/or goodwill are allocated across multiple cash-generating units.

In situations where portions of corporate assets cannot be allocated to individual CGUs on a ‘reasonable and consistent’ basis, the impairment process unfolds on two levels:

- Firstly, each CGU exhibiting signs of impairment is tested individually. Any impairment loss is then allocated to the assets within these CGUs.

- Subsequently, the smallest group of CGUs to which a portion of the corporate asset’s carrying amount can be reasonably allocated is tested for impairment. Any impairment loss is allocated in accordance with IAS 36.104.

If there’s an indication of impairment for a CGU within a group that includes goodwill, the affected CGU is tested first. Any impairment loss for that unit is recognised before assessing the larger group of units with the allocated goodwill (IAS 36.97-98). Impairment losses identified in CGUs containing goodwill are first allocated to goodwill, then proportionally to the remaining assets based on their carrying amounts. Nonetheless, an asset’s revised value post-impairment cannot fall below its FVLCD or nil. Any excess impairment loss that would have reduced the asset’s value further is reallocated to the other assets within the CGU (IAS 36.104-105).

After recognising an impairment loss, the subsequent depreciation is adjusted to reflect the reduced carrying amounts (IAS 36.63).

IAS 36 does not outline a procedure for cases where both corporate assets and goodwill are allocated to multiple CGUs. Entities must devise a method ensuring that CGUs with impairment indications are tested prior to allocating corporate assets and goodwill. Obviously, goodwill requires an annual impairment test regardless of whether there are signs of impairment (IAS 36.90).

Example: Two-stage impairment assessment

Wave Entertainment identifies three CGUs: Virtual Reality Solutions, TV Production, and Music Streaming Services, with $10m of goodwill assigned to these CGUs.

The company noted a decline in the performance of Music Streaming Services over the past six months, signalling potential impairment. This CGU’s assets, with carrying amount at $30 million, were tested for impairment and found to have a recoverable amount of $28 million. This led to recognising a $2 million impairment loss, which was proportionally assigned to the assets within the Music Streaming Services CGU.

Following this, Wave Entertainment tested the goodwill for impairment. The aggregate recoverable amount for the three CGUs was calculated at $75 million. This figure was then compared with the combined carrying amount of the CGUs’ assets and the allocated goodwill:

- Virtual Reality Solutions: $15 million.

- TV Production: $25 million.

- Music Streaming Services: $28 million (post-impairment).

- Goodwill: $10 million.

- Total carrying amount of the assets under test: $78 million.

- Recoverable amount of the CGUs: $75 million.

- Incurred impairment loss: $3 million.

To summarise, Wave Entertainment recognised a cumulative impairment loss of $5 million, comprising a $2 million loss on assets within the Music Streaming Services CGU and a $3 million impairment of goodwill.

Example: Impairment loss allocation for an underperforming asset

Astra Engineering conducts an impairment review on its Aircraft Manufacturing CGU. The CGU’s carrying amount stands at $10 million, with no goodwill allocated, and its estimated recoverable amount is $9 million, resulting in impairment. Management proposes to allocate the $1 million impairment loss by assigning $0.4 million to an outdated production line that still operates, albeit less efficiently than others. They intend to distribute the remaining $0.6 million among the remaining assets proportionally.

However, Astra Engineering cannot allocate $0.4 million for the outdated production line. Since the asset is part of the impaired CGU, it does not generate independent cash inflows. Moreover, its value in use cannot be estimated to be close to its FVLCD, as it still contributes to the CGU’s cash inflows. Therefore, the impairment loss must be allocated across all assets relative to their book values. It is essential, though, to reassess the useful life of the outdated production line.

Note, the approach would differ if the production line was out of operation.

Subsidiaries with non-controlling interests

For a CGU under impairment review that includes a subsidiary with non-controlling interests, reference Appendix C of IAS 36 and Examples 7A-7C for guidance. Specifically, when non-controlling interests are not measured at fair value, it’s crucial to ensure that the goodwill for impairment testing is grossed-up to include the non-controlling interests’ share.

Investments in subsidiaries and separate financial statements

Consider Construct All, which owns two subsidiaries, Max Contractors and Design Studios, and also directly holds other non-financial assets. In its group financial statements, there’s a single CGU comprising its direct assets and those of its subsidiaries.

In its separate financial statements, can Construct All identify the same CGU, now incorporating its directly held assets and investments in Max Contractors and Design Studios? The answer is affirmative. Although IAS 36 doesn’t explicitly cover this scenario, its general principles imply that the investments in subsidiaries do not generate independent cash inflows. While dividends from Max Contractors and Design Studios are distinct, their value is intertwined with the assets directly owned by Construct All.

IAS 28.43 addresses similar issue for investments in associates and joint ventures. Note, however, that the CGU’s book value will differ in the separate financial statements, as the assets held by subsidiaries are substituted by investment values, usually measured at cost as per IAS 27.10(a).

More about IAS 36

See other pages relating to IAS 36:

Impairment Framework for Non-Financial Assets

Value in Use as the Recoverable Amount

Impairment of Assets: Disclosure